HOLINESS ROOTED IN GRACE

The Transcendent Splendor of Divine Sanctity

INTRODUCTION: THE UNAPPROACHABLE LIGHT

"Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!" — Isaiah 6:3

In the vast expanse of divine attributes revealed in Scripture, none is more fundamental to the character of YHWH than His holiness. The thrice-repeated declaration of the seraphim—"Holy, holy, holy"—reflects an attribute of such transcendent magnitude that human language strains under the weight of its expression. Holiness is not merely one divine characteristic among many; it is the essential nature from which all other attributes flow.

Yet this holiness, so absolute in its purity and so blinding in its perfection, does not stand in isolation from the covenant grace previously explored. Rather, divine holiness and covenant grace exist in a profound relationship—each illuminating and magnifying the other. God's holiness renders His grace astonishing; His grace makes His holiness approachable.

This treatise explores the multifaceted dimensions of divine holiness, built upon the foundation of covenant grace, love, and faithfulness. We will journey from the burning sands of Sinai to the blood-soaked hill of Calvary, from the veiled Holy of Holies to the torn curtain of the temple, tracing the revelation of God's holiness and its transformative implications for those who bear His image.

We will see how all creation stands unrighteous before the perfect standard of divine holiness—even the unfallen angels who would face eternal judgment for a single transgression. And we will explore how grace, available not to angels but to the seed of Abraham, becomes God's means of imputing righteousness in this age to establish everlasting righteousness in the age to come.

Above all, we will stand in awe before the Holy One of Israel, who dwells "in unapproachable light" (1 Timothy 6:16) yet invites us to "be holy, for I am holy" (Leviticus 11:44; 1 Peter 1:16).

PART I: THE TRANSCENDENT HOLINESS OF YHWH

The Essential Nature of Divine Holiness

The Hebrew word for holy, qadosh, and its Greek equivalent, hagios, convey the fundamental concept of separation or distinctness. But divine holiness transcends mere separation. God's holiness represents His absolute otherness—His transcendent distinctness from everything created.

This holiness encompasses several dimensions:

- Ontological Holiness: God's essential being is utterly unique—"Who is like you, O LORD, among the gods? Who is like you, majestic in holiness?" (Exodus 15:11)

- Moral Holiness: God's perfect righteousness and absolute purity—"You who are of purer eyes than to see evil and cannot look at wrong" (Habakkuk 1:13)

- Glorious Holiness: God's overwhelming splendor and majesty—"Holy and awesome is his name" (Psalm 111:9)

- Sovereign Holiness: God's absolute authority over all creation—"There is none holy like the LORD: for there is none besides you" (1 Samuel 2:2)

Rudolf Otto captured an aspect of this divine holiness in his concept of the mysterium tremendum et fascinans—the "fearful and fascinating mystery" that simultaneously repels in its terrifying otherness and attracts in its compelling beauty. God's holiness both thunders in judgment and whispers in love; it both blinds in its brilliance and heals in its warmth.

The Unattainable Standard: All Creation Falls Short

When measured against the perfect holiness of YHWH, all creation—from the highest angel to the lowliest creature—falls infinitely short. As Paul declares: "All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God" (Romans 3:23).

This universal shortfall applies even to beings who have never sinned:

- Unfallen Angels: Despite their sinlessness, even the holy angels "cover their faces" before God (Isaiah 6:2), acknowledging the infinite gap between their derived holiness and God's essential holiness

- Celestial Bodies: Though magnificent, "even the heavens are not pure in his sight" (Job 15:15)

- Cosmic Powers: Though mighty, they "fall down before him who sits on the throne and worship him who lives forever and ever" (Revelation 4:10)

- Righteous Humans: Though blameless by human standards, even Job declared, "I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees you; therefore I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes" (Job 42:5-6)

The critical distinction between angelic and human fallenness highlights the unique nature of grace. For angels, a single sin results in irrevocable judgment. As Peter writes, "God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell and committed them to chains of gloomy darkness" (2 Peter 2:4). For angels, there is no provision for redemption, no opportunity for repentance, no covenant of grace.

This stark reality magnifies the wonder of grace extended to humanity. Unlike the angels, human beings—the seed of Abraham—become recipients of a grace that imputes righteousness despite repeated failure. As the writer of Hebrews notes: "For surely it is not angels that he helps, but he helps the offspring of Abraham" (Hebrews 2:16).

Holy Ground: Divine Presence Creates Sanctity

A fundamental principle of biblical holiness is that proximity to God's presence creates sanctity. This is first illustrated when Moses encounters the burning bush:

"Do not come near; take your sandals off your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground" (Exodus 3:5).

This was not inherently holy soil; it became holy because of God's manifested presence. This principle recurs throughout Scripture:

- The Tabernacle/Temple: Increasingly holy zones culminating in the Holy of Holies

- Mount Sinai: Bounded with threats of death for unauthorized approach

- The Ark of the Covenant: Bringing death to those who touched it improperly

- The Holy City: Jerusalem sanctified by God's dwelling there

- The Holy People: Israel set apart by God's election and presence

This principle reveals a profound truth: holiness is not inherent in creation but is imparted by the Creator. Nothing and no one is intrinsically holy apart from God Himself. All other holiness is derivative, dependent, and reflective.

The implications are far-reaching. If proximity to God creates sanctity, and if God is utterly holy, then how can unholy creatures approach Him without being consumed? This tension creates the central problem that the sacrificial system—and ultimately the cross—would address.

The Veiled Glory: Holiness Too Great to Behold

The transcendent holiness of God is frequently portrayed in Scripture as a glory too overwhelming for mortal comprehension. Moses, desiring to see God's glory, is told: "You cannot see my face, for man shall not see me and live" (Exodus 33:20). Even this privileged encounter required divine protection: "I will put you in a cleft of the rock, and I will cover you with my hand until I have passed by" (Exodus 33:22).

This veiling of divine holiness appears throughout Scripture:

- The Tabernacle Cloud: "The cloud covered the tent of meeting, and the glory of the LORD filled the tabernacle. And Moses was not able to enter the tent of meeting because the cloud settled on it, and the glory of the LORD filled the tabernacle" (Exodus 40:34-35)

- The Holy of Holies: Separated by a thick veil and entered only once annually with blood

- The Covered Ark: Transported under specific coverings, never to be seen directly

- The Averted Face: Even Moses could see only God's "back" but not His face

This veiling served both as protection for sinful humanity and as a sign of the separation that sin had caused. The gap between divine holiness and human sinfulness created a chasm that no human effort could cross. Any unmediated encounter between God's perfect holiness and human sinfulness would result in the annihilation of the latter.

This reality sets the stage for the greatest redemptive paradox: the Holy One who cannot dwell with sin would provide a means for sinful humans to dwell eternally in His holy presence.

PART II: HOLINESS IN THE TORAH—THE FOUNDATION

Lexical Foundations: The Semantic Field of Holiness

The Torah establishes the foundational vocabulary of holiness that would shape all subsequent biblical revelation. The Hebrew root q-d-sh appears in various forms throughout the Pentateuch, creating a rich semantic field:

- Qadosh (holy): Describing God's essential nature and what He has set apart

- Qodesh (holiness/sanctuary): The quality of being set apart for divine purposes

- Qadash (to sanctify/consecrate): The act of setting apart for sacred use

- Miqdash (sanctuary): The place set apart for divine-human encounter

This terminology reveals that holiness in the Torah is fundamentally relational—it describes the unique relationship between God and what He has set apart for Himself. Whether applied to days (Sabbath), spaces (Tabernacle), objects (altar), or people (priests), holiness always signifies special relationship to the divine.

The semantic range also reveals that holiness has both a negative and a positive aspect:

- Negative: Separation from the common, profane, or impure

- Positive: Dedication to God and His purposes

This dual nature of holiness—separation from and dedication to—shapes the entire Levitical system and prefigures the New Testament understanding of holiness as both moral purity and devoted service.

Sinai: The Paradigmatic Revelation of Holiness

The Sinai theophany (Exodus 19-20) provides the paradigmatic revelation of divine holiness in the Torah. This encounter established patterns that would define Israel's understanding of holiness:

- Physical Boundaries: "You shall set limits for the people all around, saying, 'Take care not to go up into the mountain or touch the edge of it. Whoever touches the mountain shall be put to death'" (Exodus 19:12)

- Ritual Preparation: "Go to the people and consecrate them today and tomorrow, and let them wash their garments" (Exodus 19:10)

- Overwhelming Manifestation: "Mount Sinai was wrapped in smoke because the LORD had descended on it in fire. The smoke of it went up like the smoke of a kiln, and the whole mountain trembled greatly" (Exodus 19:18)

- Mediated Communication: "The people stood far off, while Moses drew near to the thick darkness where God was" (Exodus 20:21)

This Sinai paradigm established that divine holiness is:

- Dangerous: Requiring strict boundaries

- Transformative: Requiring preparation

- Overwhelming: Beyond full human comprehension

- Mediated: Requiring an intermediary

These patterns would be recapitulated throughout Israel's worship system and find their ultimate fulfillment in Christ, who would both maintain and transform this understanding of holiness.

The Levitical System: Navigating the Holy

The Levitical system provided Israel with a comprehensive framework for navigating the dangerous terrain of divine holiness. This elaborate system addressed the fundamental question: How can an unholy people dwell in the presence of a holy God?

The answer involved multiple dimensions:

- Spatial Holiness: The Tabernacle/Temple with concentric zones of increasing holiness

- The Court: Accessible to ritually clean Israelites

- The Holy Place: Accessible only to priests

- The Holy of Holies: Accessible only to the high priest, once per year

- Temporal Holiness: Sacred times set apart from ordinary days

- Weekly: The Sabbath

- Monthly: New Moon celebrations

- Annually: The appointed feasts, culminating in Yom Kippur

- Personal Holiness: Distinctions among the people

- The High Priest: Highest human holiness

- The Priests: Set apart for divine service

- The Levites: Assistants to the priests

- The People: Set apart from other nations

- Ritual Holiness: Ceremonies maintaining the boundaries

- Sacrifices: Removing the defilement of sin

- Purifications: Addressing ritual uncleanness

- Consecrations: Setting apart for divine service

Each of these dimensions created a system of gradated holiness—a carefully structured approach to the divine presence that both protected Israel from the danger of unmediated holiness and prepared them for eventual closer communion with God.

Clean and Unclean: The Binary of Holiness

Central to the Torah's system of holiness is the binary distinction between clean (tahor) and unclean (tame). While seemingly focused on physical conditions and ritual states, this binary actually served profound theological purposes:

- Pedagogical Function: Teaching Israel to "distinguish between the holy and the common, and between the unclean and the clean" (Leviticus 10:10)

- Symbolic Function: Representing moral categories through physical analogies

- Separating Function: Distinguishing Israel from surrounding nations

- Protective Function: Creating boundaries around the sacred

The clean/unclean system established that approaching holiness required preparation and purification. Uncleanness was not primarily moral (though it could symbolize moral impurity) but ritual—a state of being unsuited for encounter with the divine.

Key principles emerged from this system:

- Contagion: Uncleanness was communicable through contact

- Temporality: Most forms of uncleanness were temporary, not permanent

- Gradation: Some forms of uncleanness were more severe than others

- Restoration: Purification rituals could restore cleanness

This system created a profound awareness that divine holiness demands human transformation. One could not simply approach God in any condition; preparation was required. Yet crucially, the system also provided the means for that preparation, foreshadowing the grace that would ultimately make holiness accessible to all.

"Be Holy, For I Am Holy": The Ethical Dimension

While much of Levitical holiness focuses on ritual and ceremonial aspects, the Torah also establishes a profound ethical dimension to holiness. The command "You shall be holy, for I the LORD your God am holy" (Leviticus 19:2) introduces a chapter filled primarily with ethical rather than ceremonial instructions.

This ethical holiness includes:

- Reverence for Parents: "Every one of you shall revere his mother and his father" (Leviticus 19:3)

- Care for the Vulnerable: "When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap your field right up to its edge, neither shall you gather the gleanings after your harvest... You shall leave them for the poor and for the sojourner" (Leviticus 19:9-10)

- Justice in Business: "You shall not steal; you shall not deal falsely; you shall not lie to one another" (Leviticus 19:11)

- Love of Neighbor: "You shall love your neighbor as yourself" (Leviticus 19:18)

This ethical dimension reveals that holiness is not merely ritualistic separation but moral transformation—becoming like God in character while acknowledging the unbridgeable distinction in essence. Israel was to reflect divine holiness through ethical behavior, not just ritual precision.

This understanding challenges any artificial separation between ceremonial and moral law. In the Torah, both dimensions express the same fundamental reality: holiness involves being set apart for relationship with God, and that relationship transforms every aspect of life.

PART III: HOLINESS AND COVENANT GRACE

The Paradox of the Holy God's Covenant Love

The Torah presents what appears to be an irresolvable paradox: the utterly holy God enters into covenant relationship with a sinful people. This paradox is central to biblical revelation and creates the tension that drives the entire redemptive narrative.

The puzzle has several dimensions:

- The Proximity Problem: How can an utterly holy God dwell among an unholy people? "I will dwell among the people of Israel and will be their God" (Exodus 29:45)

- The Persistence Problem: How can a holy God maintain covenant faithfulness despite human unfaithfulness? "If we are faithless, he remains faithful—for he cannot deny himself" (2 Timothy 2:13)

- The Purification Problem: How can unholy people become holy enough for communion with God? "Who shall ascend the hill of the LORD? And who shall stand in his holy place? He who has clean hands and a pure heart" (Psalm 24:3-4)

This paradox reveals that holiness and grace are not opposed but interrelated. God's holiness makes His grace necessary; His grace makes His holiness accessible.

Grace as the Foundation of Covenant Holiness

The resolution to this paradox lies in understanding grace as the foundation of covenant holiness. Contrary to legalistic interpretations, the Torah itself establishes grace as prior to law:

- Election Precedes Obligation: "The LORD set his love on you and chose you... because the LORD loves you and is keeping the oath that he swore to your fathers" (Deuteronomy 7:7-8)

- Redemption Precedes Requirements: "I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery. You shall have no other gods before me" (Exodus 20:2-3)

- Presence Precedes Purification: God establishes the Tabernacle system as a means for an unholy people to dwell with a holy God

This priority of grace is embedded in the structure of the Torah itself. The narrative of redemption from Egypt precedes the giving of the Law. God does not say, "If you keep these commandments, I will redeem you from Egypt." Rather, He declares, "I have redeemed you from Egypt; therefore, keep these commandments."

This grace-based foundation transforms our understanding of Levitical holiness. The sacrificial system was not a means of earning God's favor but a gracious provision for maintaining the covenant relationship already established by divine initiative.

The Tabernacle: Grace Creating Sacred Space

The Tabernacle represents the physical embodiment of grace creating sacred space. This divine accommodation—God limiting His omnipresence to dwell in a specific location among His people—represents grace of the highest order.

The Tabernacle's design reveals several principles of grace-based holiness:

- Divine Initiative: God provides the design, the materials, and even the skills needed (Exodus 31:1-11)

- Mediated Presence: The complex structure mediates between divine holiness and human sinfulness

- Gracious Proximity: The Holy of Holies brings God's presence remarkably close to His people while maintaining necessary separation

- Symbolic Atonement: The elaborate sacrificial system provides a way for sinful people to approach a holy God

The very existence of the Tabernacle represented extraordinary grace. Rather than requiring Israel to ascend to heaven (impossible) or manifesting His unmediated presence (fatal), God created a system in which His holiness could dwell among His people without destroying them.

As the Gospel of John would later describe in Christological terms: "The Word became flesh and tabernacled among us, and we have seen his glory" (John 1:14, literal translation). The incarnation would perfect what the Tabernacle foreshadowed: grace creating sacred space within the human realm.

Law as Grace: Torah as Divine Gift

Contrary to later mischaracterizations, the Torah presents the Law itself as an expression of divine grace—a gift rather than a burden. As Moses declares:

"What great nation is there that has statutes and rules so righteous as all this law that I set before you today?" (Deuteronomy 4:8)

This grace-based understanding of Torah appears in several dimensions:

- Revelatory Grace: The Law reveals God's character and will, removing the need for human speculation

- Protective Grace: The commandments serve as boundaries protecting Israel from harm

- Distinction Grace: The Law marks Israel as God's special possession among the nations

- Wisdom Grace: The commandments provide practical guidance for flourishing human life

- Relationship Grace: The Law defines the terms of covenant relationship with God

The Psalms particularly celebrate this gracious aspect of Torah. Psalm 19 describes the Law as "more desirable than gold" and "sweeter than honey." Psalm 119, the longest chapter in the Bible, offers an extended meditation on the Law as a delight rather than a burden.

This grace-based understanding of Law resolves the apparent tension between holiness requirements and human inability. The Law was never intended as a means of earning relationship with God but as the loving guidance of a Father to His children already in relationship with Him through grace.

Imputed Righteousness in the Old Testament

While often considered a New Testament concept, the imputation of righteousness—counting as righteous those who believe—is foundational to Old Testament covenant grace. As Genesis 15:6 declares of Abraham: "He believed the LORD, and he counted it to him as righteousness."

This pattern of imputed righteousness appears throughout the Old Testament:

- Substitutionary Atonement: The sacrificial system allowed for the symbolic transfer of sin to an innocent victim

- Priestly Representation: The high priest bore the names of the twelve tribes before the Lord

- Covenant Identification: Israel collectively treated according to covenant terms rather than individual merit

- Prophetic Hope: The promised "righteous branch" who would be called "The LORD our righteousness" (Jeremiah 23:5-6)

This imputation of righteousness provided the foundation for covenant relationship. Israel could approach the holy God not on the basis of their own righteousness but through the gracious provision of an alternate righteousness—ultimately pointing to Christ, who would become "our righteousness, holiness and redemption" (1 Corinthians 1:30).

PART IV: HOLINESS IN THE PROPHETS AND WRITINGS

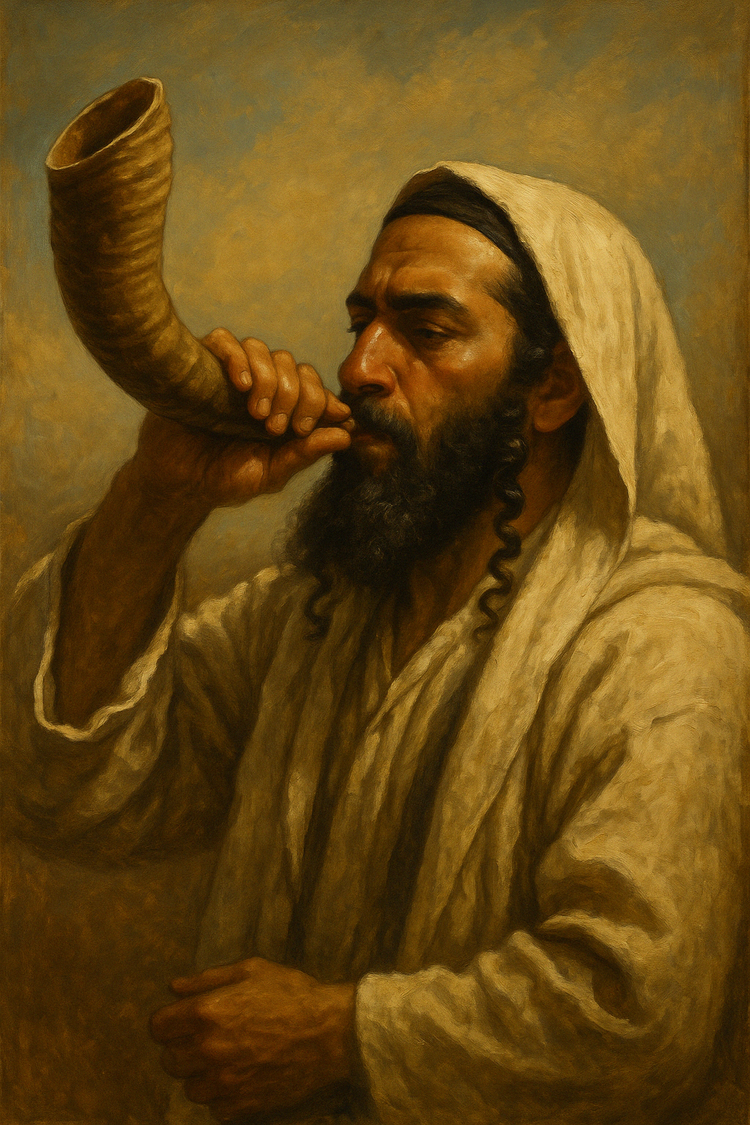

Isaiah's Vision: The Holy One of Israel

No prophet emphasizes divine holiness more than Isaiah. His inaugural vision in the temple (Isaiah 6) provides one of Scripture's most powerful revelations of divine holiness:

"I saw the Lord sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up; and the train of his robe filled the temple. Above him stood the seraphim... And one called to another and said: 'Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!'" (Isaiah 6:1-3)

Isaiah's response—"Woe is me! For I am lost; for I am a man of unclean lips" (Isaiah 6:5)—represents the appropriate human reaction to divine holiness: recognition of utter unworthiness.

Yet the vision doesn't end with this recognition. A seraph touches Isaiah's lips with a burning coal from the altar, declaring: "Your guilt is taken away, and your sin atoned for" (Isaiah 6:7). This symbolic purification illustrates the central biblical pattern: divine holiness first exposes human sin, then graciously provides for its removal.

Isaiah develops this theme throughout his prophecy, referring to God as "the Holy One of Israel" twenty-five times. This title emphasizes both God's absolute distinctness and His covenant relationship with His people—capturing the paradox of transcendent holiness in intimate relationship.

Ezekiel's Temple: Holiness Restored

Ezekiel's elaborate vision of a restored temple (Ezekiel 40-48) provides the most comprehensive prophetic picture of holiness renewed after judgment. Writing from Babylonian exile after the destruction of Solomon's temple, Ezekiel envisions a future restoration of sacred space.

This vision contains several key elements:

- The Return of Divine Glory: "The glory of the LORD entered the temple by the gate facing east" (Ezekiel 43:4)—reversing the earlier departure of glory (Ezekiel 10-11)

- Increased Sanctity: Stricter divisions between holy and common than in the first temple

- Supernatural Transformation: A river flowing from the temple bringing healing and life (Ezekiel 47:1-12)

- Divine Presence as Central: "The name of the city from that time on shall be, The LORD Is There" (Ezekiel 48:35)

Ezekiel's vision reveals that holiness is not merely about separation but about transformation. The restored temple becomes a source of healing for the nations, with the river of life flowing outward to transform even the Dead Sea into fresh water.

This expansive vision points toward the New Testament fulfillment, where holiness becomes not merely confined to a physical temple but flows outward through the people of God to bring healing to the nations.

Psalms: Worshiping the Holy One

The Psalms provide Israel's response to divine holiness through worship. Unlike the Law and Prophets, which primarily represent God's voice to humanity, the Psalms represent humanity's voice to God—often in response to His revealed holiness.

Several patterns emerge in the Psalms' treatment of holiness:

- Awe-Filled Worship: "Worship the LORD in the splendor of holiness; tremble before him, all the earth!" (Psalm 96:9)

- Confident Approach: "O LORD, who shall sojourn in your tent? Who shall dwell on your holy hill?" (Psalm 15:1)—followed by ethical rather than merely ritual qualifications

- Holiness as Beauty: "Worship the LORD in the beauty of holiness" (Psalm 29:2 KJV)

- Holiness as Character: "The LORD is righteous in all his ways and kind in all his works" (Psalm 145:17)

The Psalms reveal that holiness, while fearsome, is not meant to keep worshipers at a distance but to draw them into transformative encounter. This approach-oriented worship anticipates the New Testament's invitation to "draw near with a true heart in full assurance of faith" (Hebrews 10:22).

Wisdom Literature: Holiness in Everyday Life

The Wisdom Literature extends the concept of holiness beyond ritual and worship into everyday ethical living. Books like Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Job explore how the holy God's character should shape ordinary human existence.

Key principles emerge:

- The Fear of the Lord: "The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom" (Proverbs 9:10)—reverence for divine holiness as the foundation of wise living

- Integrity in Business: "A false balance is an abomination to the LORD, but a just weight is his delight" (Proverbs 11:1)

- Sexual Purity: "Let your fountain be blessed, and rejoice in the wife of your youth" (Proverbs 5:18)

- Truthful Speech: "Lying lips are an abomination to the LORD, but those who act faithfully are his delight" (Proverbs 12:22)

This wisdom tradition extends holiness beyond the Temple precincts into the marketplace, the home, and the community. It establishes that holiness is not compartmentalized but comprehensive—encompassing all of life under divine sovereignty.

PART V: HOLINESS IN CHRIST—THE FULFILLMENT

The Incarnation: Holiness Embodied

The incarnation represents the most astonishing development in the biblical revelation of holiness. The utterly transcendent Holy One takes on human flesh, bringing divine holiness into direct contact with human existence.

This incarnational holiness transforms previous understandings in several ways:

- Immanence Without Compromise: Christ is "holy, innocent, unstained, separated from sinners" (Hebrews 7:26) yet eats with sinners and touches the unclean

- Contagious Holiness: Unlike ritual impurity which spreads by contact, Jesus' holiness spreads to others—"Who touched me? For I perceive that power has gone out from me" (Luke 8:45-46)

- Holiness as Compassion: "When he saw the crowds, he had compassion for them" (Matthew 9:36)—revealing divine holiness as deeply concerned with human suffering

- Holiness Without Fear: "Take heart, it is I. Do not be afraid" (Matthew 14:27)—inviting approach rather than distance

In Christ, holiness becomes not merely a standard that condemns but a power that transforms. The incarnation reveals that divine holiness, while maintaining its absolute purity, seeks not separation from sinners but their redemption and restoration.

The Crucifixion: Holiness and Judgment United

The cross represents the ultimate convergence of divine holiness and covenant grace. At Calvary, God's absolute holiness and His boundless love meet in a single event of cosmic significance.

This convergence resolves the biblical tension in several dimensions:

- Justice Fulfilled: "God put forward [Christ] as a propitiation by his blood... to show God's righteousness" (Romans 3:25)—divine holiness fully expressed in judgment

- Love Demonstrated: "God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us" (Romans 5:8)—divine grace fully expressed in sacrifice

- Separation Overcome: "In Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ" (Ephesians 2:13)—the barrier of holiness bridged

- Law Satisfied: "Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us" (Galatians 3:13)—the demands of holiness met

The cross reveals that divine holiness is not compromised by grace; rather, grace flows precisely from the absolute nature of divine holiness. Because God is utterly holy, the price of sin must be paid completely. Because God is utterly loving, He pays that price Himself.

The Resurrection: Holiness Victorious

The resurrection declares divine holiness victorious over sin, death, and corruption. Christ rises not merely as a spiritual being but with a transformed physical body—establishing that divine holiness claims jurisdiction over physical creation.

This resurrection holiness has several implications:

- Creation Affirmed: Physical matter is not inherently unholy but capable of bearing divine glory

- Death Defeated: That which most vividly symbolizes the consequences of sin is overcome

- Holiness Embodied: The resurrection body becomes the pattern for believers' future transformation

- New Creation Inaugurated: "If anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation" (2 Corinthians 5:17)

The resurrection reveals that divine holiness is not merely separative but transformative and re-creative. God's ultimate purpose is not to abandon the physical creation as hopelessly corrupted but to purify and transform it—making all things new and bring all things under the dominion of His holiness.

Pentecost: Holiness Indwelling

Pentecost represents the most revolutionary development in the biblical revelation of holiness: the Holy Spirit indwelling believers, making them temples of divine presence.

This indwelling holiness transforms previous paradigms:

- Internal vs. External: "I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts" (Jeremiah 31:33)—fulfilling Jeremiah's prophecy of internalized covenant

- Universal vs. Restricted: "I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh" (Joel 2:28)—extending sacred anointing beyond priests to all believers

- Permanent vs. Temporary: "He will give you another Helper, to be with you forever" (John 14:16)—establishing an enduring divine presence

- Corporate vs. Individual: "Do you not know that you [plural] are God's temple and that God's Spirit dwells in you [plural]?" (1 Corinthians 3:16)—creating a community of divine presence

Pentecost completes the trajectory from Mount Sinai (where approaching God's holiness brought death) to Mount Zion (where God's holiness dwells within believers, bringing life). The boundaries that once protected Israel from divine holiness now become channels through which that holiness flows to transform believers from the inside out.

PART VI: HOLINESS IN THE BELIEVER—THE APPLICATION

Positional Holiness: "In Christ"

The New Testament introduces a revolutionary concept: believers possess a "positional holiness" based not on their own character but on their identification with Christ. This concept, expressed most frequently in Paul's phrase "in Christ," transforms the entire framework of holiness.

This positional holiness has several dimensions:

- Imputed Righteousness: "For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God" (2 Corinthians 5:21)

- Complete Acceptance: "He has blessed us in Christ with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places" (Ephesians 1:3)

- Holy Standing: "To the church of God that is in Corinth, to those sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints" (1 Corinthians 1:2)—writing to a church with significant moral problems

- Perfect Holiness in Christ: "By a single offering he has perfected for all time those who are being sanctified" (Hebrews 10:14)

This positional holiness creates the radical security of the New Covenant. Believers approach God not on the basis of their personal holiness but on the basis of Christ's perfect holiness credited to them through faith.

This position resolves the tension between divine holiness and human sinfulness. The believer "in Christ" can stand before the Holy One not because they have achieved moral perfection but because they are clothed in Christ's perfect righteousness.

Progressive Sanctification: Becoming What We Are

While positional holiness is complete and perfect from the moment of salvation, experiential holiness—or sanctification—is progressive and ongoing. The New Testament presents this paradoxical reality: believers are already holy in position while becoming holy in practice.

This progressive sanctification operates on several principles:

- Cooperation with Divine Agency: "Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling, for it is God who works in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure" (Philippians 2:12-13)

- Transformation by Beholding: "We all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another" (2 Corinthians 3:18)

- Mind Renewal: "Be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect" (Romans 12:2)

- Mortification of Sin: "Put to death therefore what is earthly in you: sexual immorality, impurity, passion, evil desire, and covetousness, which is idolatry" (Colossians 3:5)

- Cultivation of Virtue: "Put on then, as God's chosen ones, holy and beloved, compassionate hearts, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience" (Colossians 3:12)

Progressive sanctification reveals that holiness is not merely a status to be celebrated but a calling to be pursued. As Peter writes, "As he who called you is holy, you also be holy in all your conduct" (1 Peter 1:15).

Crucially, this pursuit is not legalistic striving but grateful response—not an attempt to earn God's favor but an expression of having already received it. The motivation for holiness is not fear of rejection but love for the One who has already accepted us in Christ.

The Holy Spirit: The Agent of Sanctification

Progressive sanctification is fundamentally the work of the Holy Spirit. Unlike the self-improvement programs of human religion, biblical holiness depends on the indwelling presence of God Himself.

The Spirit's sanctifying work operates in several dimensions:

- Conviction of Sin: "When he comes, he will convict the world concerning sin and righteousness and judgment" (John 16:8)

- Illumination of Truth: "When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth" (John 16:13)

- Inner Transformation: "The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control" (Galatians 5:22-23)

- Divine Empowerment: "You will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you" (Acts 1:8)

- Glorification of Christ: "He will glorify me, for he will take what is mine and declare it to you" (John 16:14)

This Spirit-dependence distinguishes Christian holiness from all forms of legalism and moralism. True holiness is not achieved through human effort but received as divine gift, cultivated through relationship, and expressed in grateful obedience.

The believer's role is not passive but cooperative—"Keep in step with the Spirit" (Galatians 5:25). We actively participate in what the Spirit is doing, neither passive recipients nor autonomous actors but covenant partners in the work of sanctification.

The Community of the Holy: Ecclesial Holiness

Biblical holiness is not merely individual but communal. The New Testament consistently addresses holiness in the context of the church—the community set apart for God's purposes.

This ecclesial dimension of holiness appears in several ways:

- Corporate Identity: "You are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession" (1 Peter 2:9)

- Mutual Edification: "Let us consider how to stir up one another to love and good works" (Hebrews 10:24)

- Shared Discipline: "If anyone is caught in any transgression, you who are spiritual should restore him in a spirit of gentleness" (Galatians 6:1)

- Collective Witness: "Let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven" (Matthew 5:16)

- Corporate Worship: "Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teaching and admonishing one another in all wisdom, singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs" (Colossians 3:16)

This communal emphasis challenges Western individualism, which often reduces holiness to personal piety divorced from covenant community. Biblical holiness creates not merely holy individuals but a holy people—a community that collectively displays the character of God to the watching world.

The church becomes the "temple of the Holy Spirit" (1 Corinthians 3:16) corporately, with each member contributing to the sanctity of the whole body. Individual holiness matters not merely for personal salvation but for the integrity of the community's witness.

PART VII: HOLINESS AND THE NEW CREATION

The Already and Not Yet: Present Tension

The New Testament presents holiness in a framework of "already but not yet"—believers are already positionally holy while not yet experientially perfect. This tension creates the distinctive character of Christian life in the present age.

This tension appears in several dimensions:

- Justification and Sanctification: Already declared righteous, not yet morally perfect

- Indwelling and Struggle: Already having the Spirit, not yet fully controlled by the Spirit

- New Creation and Old Creation: Already new creations in Christ, not yet fully transformed

- Kingdom Come and Coming: Already citizens of God's kingdom, not yet experiencing its fullness

This tension is not a problem to be resolved but a reality to be embraced. It explains why believers simultaneously rejoice in their perfect acceptance while groaning under ongoing struggles with sin. As Paul confesses, "Not that I have already obtained this or am already perfect, but I press on to make it my own, because Christ Jesus has made me his own" (Philippians 3:12).

This "already/not yet" framework preserves both the assurance of grace and the call to holiness. We pursue holiness not to become God's children but because we already are His children; not to earn His love but because we have already received it.

Angels, Humans, and Future Glory

The comparison between angels and humans highlights the unique destiny of redeemed humanity. While unfallen angels have maintained their original holiness, they do not experience the transformative grace available to fallen humans.

This distinction has several dimensions:

- Angels Maintain, Humans Transform: Angels preserve their created holiness; humans experience redemptive transformation

- Angels Serve, Humans Inherit: "Are they not all ministering spirits sent out to serve for the sake of those who are to inherit salvation?" (Hebrews 1:14)

- Angels Observe, Humans Experience: Angels "long to look" into the gospel (1 Peter 1:12) while humans experience its power

- Angels Remain, Humans Elevate: Humans in resurrection will be exalted above angels—"Do you not know that we are to judge angels?" (1 Corinthians 6:3)

This comparison reveals the astounding trajectory of human holiness. Through redemption in Christ, fallen humans will ultimately attain a glory that unfallen angels do not share—not merely restored to pre-Fall innocence but elevated to Christ-like splendor.

As John writes, "Beloved, we are God's children now, and what we will be has not yet appeared; but we know that when he appears we shall be like him, because we shall see him as he is" (1 John 3:2).

Cosmic Restoration: All Things Made Holy

The ultimate scope of holiness extends beyond individual believers to encompass the entire created order. God's redemptive purpose is not merely to save individual souls but to restore all creation to its intended glory.

This cosmic restoration appears in several biblical passages:

- Creation's Redemption: "The creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God" (Romans 8:21)

- Universal Purification: "Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away" (Revelation 21:1)

- Comprehensive Renewal: "Behold, I am making all things new" (Revelation 21:5)

- God's All-Encompassing Presence: "The dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God" (Revelation 21:3)

This cosmic vision reveals that holiness is not about escaping creation but about transforming it. The material world is not inherently unholy but is capable of bearing divine glory when purified and renewed.

The trajectory moves from the restricted holiness of the Holy of Holies to the universal holiness of the new creation, where "the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the LORD as the waters cover the sea" (Habakkuk 2:14).

The River of Life: Holiness Flowing Outward

The Bible concludes with a vision that perfectly captures the ultimate purpose of holiness: not separation but transformation, not restriction but expansion, not exclusion but invitation.

"Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, bright as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb through the middle of the street of the city; also, on either side of the river, the tree of life with its twelve kinds of fruit, yielding its fruit each month. The leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations" (Revelation 22:1-2).

This river of life represents divine holiness flowing outward to bring healing and life wherever it goes—echoing Ezekiel's vision of the river flowing from the temple. Several elements are significant:

- Source in Divine Presence: The river flows "from the throne of God and of the Lamb"—holiness originates in God Himself

- Central Position: The river flows "through the middle of the street"—holiness is central, not peripheral

- Life-Giving Quality: The "tree of life" grows alongside—holiness produces abundant life

- Healing Purpose: The leaves are "for the healing of the nations"—holiness brings restoration

- Universal Accessibility: "The Spirit and the Bride say, 'Come.' And let the one who hears say, 'Come.' And let the one who is thirsty come; let the one who desires take the water of life without price" (Revelation 22:17)

This final biblical image reveals that holiness ultimately serves not to exclude but to include, not to condemn but to heal, not to separate but to unite all creation under the loving sovereignty of the thrice-holy God.

CONCLUSION: GRACE-ROOTED HOLINESS

Our journey through the biblical revelation of holiness reveals a grand narrative far richer and more nuanced than simplistic understandings allow. Divine holiness is not merely a moral standard that condemns human sinfulness but a transformative presence that redeems and elevates fallen creation.

From the burning bush to the burning coal, from Sinai's boundaries to Calvary's invitation, from the restricted Holy of Holies to the universal river of life, Scripture traces the progressive revelation of holiness as both transcendent and immanent, both pure and purifying, both demanding and enabling.

Central to this revelation is the relationship between holiness and grace. Far from being opposed, these divine attributes exist in perfect harmony. Grace is not the suspension of holiness but its highest expression. Holiness is not the absence of grace but its ultimate purpose.

This harmony appears most clearly in Christ, the Holy One who touches lepers, embraces sinners, and extends mercy to the broken while never compromising divine purity. At the cross, divine holiness and covenant grace meet in perfect union—justice fully satisfied, love fully expressed, sin fully judged, mercy fully extended.

The practical implications are profound:

- Reverent Confidence: We approach God with both reverence for His holiness and confidence in His grace

- Grateful Obedience: We pursue holiness not to earn acceptance but because we have already been accepted

- Humble Dependence: We rely not on our own moral strength but on the indwelling Holy Spirit

- Communal Witness: We express holiness not merely as individuals but as the covenant community

- Cosmic Hope: We anticipate not merely personal salvation but the restoration of all creation

The angels, who have never sinned and would face eternal judgment for a single transgression, marvel at the grace extended to humanity. They observe with wonder as God not merely forgives human sin but transforms sinners into the very image of His Son—taking what was most corrupted and making it most glorious.

We who have received this grace stand in the extraordinary position of experiencing what angels can only observe—the transformative power of divine holiness expressed through covenant grace. As Peter writes, these are "things into which angels long to look" (1 Peter 1:12). By his grace he has made us who were sin, to be holy ones--saints, through and in Jesus Christ our Lord and salvation.

In view of this our appropriate response is neither presumption nor despair but wonder and worship. We have been invited to "share in God's holiness" (Hebrews 12:10)—not through our own merit but through union with Christ, not by abandoning creation but by participating in its redemption, not by achieving moral perfection but by receiving divine transformation.

Thus we join the seraphim in their eternal declaration: "Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!" (Isaiah 6:3). But we add to their chorus the unique perspective of the redeemed: "To him who loves us and has freed us from our sins by his blood and made us a kingdom, priests to his God and Father, to him be glory and dominion forever and ever. Amen" (Revelation 1:5-6).

Soli Deo Gloria

Comments ()